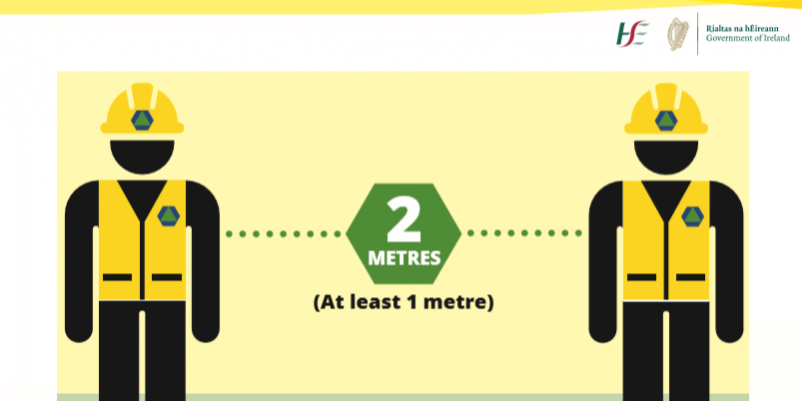

Social distancing for construction workers/Photo credit: CIF/ www.constructionnews.ie

Authors: Truman Packard and Michael Weber

COVID-19 (Coronavirus) will liquidate livelihoods. In a catastrophic shock, concerns for income and wealth inequality, which inform anti-poverty programs in “normal” times, must take a back seat to concerns with livelihood losses. Right now, the risks of contagion and loss of life are the main worry. But countries will soon enter a phase when the effects of the crisis on livelihoods become similarly pressing. In fact, for many informal workers in low- and middle-income countries, this is already the case, as recent reports from India attest.

But the employment measures being hastily deployed by governments, won’t reach informal workers. Policy responses such as cheaper, easier credit for firms, furloughs, and wage subsidies could preserve many jobs and help ease anxieties about the economic costs of social distancing. And public risk-pooling mechanisms, like unemployment insurance (UI), are also being put to the test. Governments offer UI because markets won’t do so. These approaches are all discussed in other blogs in this series.

But for workers without stable tenure and an employer to make contributions, wage subsidies won’t help; and access to UI is scant. So, these workers lack a protective cushion to smooth their consumption; and their economies lack an automatic “stabilizer” to help demand bounce back. Although informal work has long been the norm in low- and middle-income countries, the growth of the gig work in high-income countries presents similarly urgent challenges to policymakers in Paris, Seoul and Washington DC.

Labor-intensive public works are part of the solution. If the COVID-19 (Coronavirus) contraction becomes “U” shaped with a slow recovery, many informal workers could lose their livelihoods for a long time. To protect them, governments can launch or expand “cash-for-work” programs. Share on X Public works offer an effective way to mitigate livelihood loses while managing health risks. Such programs featured successfully in responses to the shocks and sharp rises in unemployment in the late 1990s and the global financial crisis of 2009 and 2010.

Public works programs are financed directly from governments’ general revenues (or foreign aid) so they offer protection from the largest, most resilient risk-pools available. Access is given to all in need, whatever work they have lost. Well-designed public works are the form of protection that is most likely to reach people who have lost an informal job; or the self-employed, whose livelihoods are decimated in the downturn. Throughout history, public works have functioned as a counter-cyclical social insurance instrument.

Getting the design right is crucial. Program parameters must be set to ensure broad access and the right incentives. The wage (or stipend) level is crucial to whether public works succeed in reaching those who need them; to ensuring that enough program places are available in the downturn, and to avoiding damaging distortions when labor markets recover. Often, governments make the mistake of setting public-works wages at the statutory minimum wage level. But in many low- and middle-income countries the MW is set above the market-clearing wage for unskilled labor, even in good times.

Offering above-market wages for public works imposes three separate economic costs that can hinder their impact. They attract more workers than really need assistance; they pay workers more than they would otherwise accept, and they crowd out private employment as recoveries begin. As many governments have discovered, when public works offer above-market wages, the fiscal costs can run out of control unless protection is tightly rationed. But rationing puts governments in the uncomfortable position of allocating slots through quantities and time limits, rather than through prices. Obviously, quota limits stop programs from protecting all in need.

In a pandemic, the design of public works must change. The public health threat of COVID-19 (Coronavirus) brings new challenges to deploying public works effectively – such as ensuring participants have protective equipment and that physical distancing is maintained. The Philippines’ Disadvantaged Workers Program requires participants to undergo health and safety orientation. Certainly, as news broadcast images of people disinfecting streets, sanitizing public spaces and distributing food and clean water attest, there is plenty to do. Similarly, the priority of improving connective infrastructure will grow in the aftermath of the crisis. All these newly important tasks can be undertaken while maintaining safe distances. But planning such programs takes time. Prudent governments will use the first phase of the crisis to get “public good” works projects with strong health standards “shovel ready” for when the initial viral explosion has been contained. Share on X

Digital technologies offer a new way of delivering public works safely, even during contagion. Advances in Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) will facilitate the “digitization” of public works, which helps to minimize physical contacts. An upcoming blog in this series will look at these opportunities in more detail.

This is the third blog on ways to protect workers and jobs in the COVID-19 (Coronavirus) crisis, based on a World Bank Jobs Group Note: “Managing the Employment Impacts of the COVID-19 Crisis, Policy Options for the Short Term.” Upcoming blogs will cover social assistance for income support to informal workers; the role of unemployment insurance; and policy options for the recovery phase, such as digitally-enabled public works; addressing gender dimensions of the COVID-19 (coronavirus) jobs crisis; and support for labor market reinsertion (Active Labor Market Programs).